Confession: I am prone to worry. I can be unusually preoccupied by the circumstances right in front of me. It is a battle for perspective. A struggle to keep the big picture in view.

Confession: I am prone to worry. I can be unusually preoccupied by the circumstances right in front of me. It is a battle for perspective. A struggle to keep the big picture in view.

Worry is one of the biggest enemies of vision. Because vision connects us to our calling and purpose in our work (and life in general), I worked hard to deal ruthlessly with worry—treat it like an undercover spy threatening state security or the suave sociopath asking for just a little help on his next project.

Worry does that–it threatens the good things we have going on.

Which reminds me of a funny—if embarrassing—story that illustrates this specific consequence of worry, namely the loss of context and perspective.

About 5 years ago I joined a work-sponsored city league softball team. Sure, it had been 10 years since I had played in a men’s softball league. I didn’t have any illusions that I would be tearing it up on the field (albeit a few concerns I might tear up my hammy). However, I did expect to contribute, play my part, to at least approximate my abilities, even if they were mostly in the past.

I had some reason for my confidence. As a Little Leaguer I was always selected for the all-star team, as a high school baseball player I competed at a high level, then later as a high school teacher, I coached baseball, always mixing it up with my players on the field through hitting and fielding drills. And, for about 10 years after college I had played centerfield for our city league softball team, where I tracked down deep fly balls and turned singles into doubles as I competed against other weekend-warrior 20 and 30-somethings, all of us in trying to recapture a glimpse of former glories.

In fact, I figured I had enough experience under my belt to jump right back onto the field, and frankly, do “more than my part” for the team. Call it confident expectation.

Pride comes before the fall. Or, more to the point, “Pride comes before the dropped fly ball.”

Here’s how it played out: I had spent my workday like most workdays writing and editing an article that I was finishing up. As a policy analyst (one of many varied jobs I’ve had over the years), a big part of my workday was spent staring at a computer screen. Certainly not a physically taxing way to spend the day. But there was a downside, which you’ll see in a moment.

The first game arrived, and with not a little bit excitement, I went straight from the office to the field. Parking quickly and grabbing my mitt and cap, I jogged to the field, my cleats clicking on the asphalt parking lot. I saw the familiar bright green grass under the glow of the evening lights, heard the laughter and cheering from across the diamonds, and that familiar “tink” of the bat as a player swung from his heals and legged out the hit. I could even see the glisten of the evening dew on the grass.

Yes, I had missed playing softball with buddies. I hustled onto the field to warm up, and before I knew it, the game had started.

Then, I jogged out to take my place in left field. And that’s when the wheels fell off.

The second batter lifted a “routine” fly ball to the outfield. I heard it, knew in my gut it was headed my way, and scanned the sky to find the ball ascending and descending in my direction, destined for the soft leather of my awaiting glove.

Only, I couldn’t find the ball.

In those split seconds, as I drifted toward the blur that I thought I saw in the dark night sky, panic rose up in my gut… “Where is it? Where is the ball?!” And then in a flash, that ball came down from the heavens like a meteor afire diving to the earth.

And not into my mitt.

I scrambled over to retrieve the ball, then flung it in frustration to the shortstop. I shudder to imagine all over again what I must have looked like trying to catch that fly ball.

Sure, I tried to blame it on my fuzzy eyes, as I sheepishly jogged to the dugout at the end of the inning: “Wow, I think I need to wear glasses to play softball…” But there was no getting it back. I was that guy who looked like he had never played an inning of baseball beyond little kid sandlot pick-up games.

Because my eyes had become more comfortable focusing on what was right in front of me, I just couldn’t focus on objects at a distance—certainly not objects moving fast through the night sky. Fixing my eyes on circumstances right in front of me day in and day out affects my perspective, making it difficult to see the bigger picture. You could say that I “lost sight of the forest” as I fixed my attention “on the trees”—

There is a physical condition for this, of course, called myopia. Short sightedness. It’s like having blinders on, suffering from a narrow point of view, a one-track mind, you might say. All these describe a lack of perspective, physical and otherwise.

And like my experience on the softball field, worrying is exactly that—staring at the circumstances right in front of me, losing sight of the big picture.

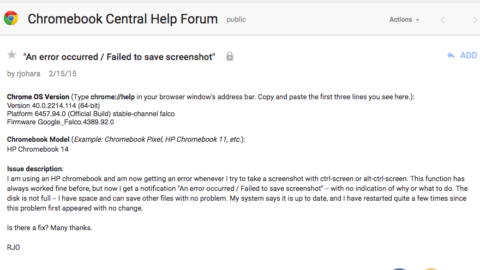

Recently I have started organizing my days again around my top priority, and I am finding these 3 ideas helpful in staying committed to the big picture: context, retrospection, and circumspection.

Context specifically is “the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea.” It makes up the “terms of which a thing can be fully understood and assessed.” Worrying occurs when we don’t take the time to consider the context. We don’t seek to understand fully or realistically the setting. We stop taking in data, understanding the bigger picture.

- A preoccupied manager doesn’t notice his colleagues’ subtle references to how unpredictable the incentive compensation is, undermining the motivating effect it’s supposed to have, while he focuses only on weekly results.

- A well-meaning but anxious CEO loses count of how many times she has changed direction, leaving her leadership team with whiplash of sorts, never stepping back to see the cost of changing direction over and over and over.

- A worried dad forgets to affirm his son for the hard work he’s doing in the classroom, focusing instead only on the 3% of missing or late assignments.

Research on literal shortsightedness—myopia—is instructive for us in understanding this challenge of perspective. Researchers point out that shortsightedness is a phenomenon of the 20th century. Pointing to findings among the Inuit Native North Americans’ older generation who had next-to-no cases of short-sightedness, they contrast this with today’s rates between 10-25% of the Inuit children needing glasses.

“Short-sightedness is an industrial disease,” says Ian Flitcroft at Children’s University Hospital, Dublin. “The research points out that while our genes may still play a role in deciding who becomes short-sighted, it was only through a change in environment that these kinds problems began to emerge.”

Here is the kicker–Researchers point to children being indoors, away from horizons and large-scale perspective, as the cause for the increase in myopia among children.

I think the same is true of our generation when it comes to worry. We stare at what’s right in front of us, lose our ability to “see” the bigger picture, and as a result, learn to live with worry.

A recent poll called this generation the most stressed out. On a 10-point scale, Americans ages 18-33 reported an average stress level of 5.4 compared to the national average of 4.9, and 52% said stress made it hard for them to sleep at night in the past month. If any adult should be sleeping well at night it’s an 18-33 year-old, but that’s no longer the case.

Like my long days spent inside staring at a computer screen, and my ensuing inability to track a fly ball soaring into the sky, I need to get outside, see the horizon, gain some perspective on the context of my life.

Here are some practical ways that I have found to do just that, which makes me a better leader and team contributor–

- Make an effort to see through the eyes of the people I am leading at work: Slow down, look the person in the eye, listen beyond the words being said in the moment for the subtext of the conversation. I do this by reminding myself that we all have roles in our lives–spouse, parent, neighbor, friend, classmate, daughter…

- Reflect on the consequences of my decisions over time on the people around me. Every decision has an impact. While all or most of us are good at considering the impact of a decision in the moment, few of us look back and learn from that decision, and still fewer connect that specifically to the people who were affected by the decision. This is the big view of decision making.

- Revisit my goals monthly. Looking at my personal and professional goals every month puts the day-to-day challenges into perspective, keeps me from losing context for why I am pushing hard through the things that make me anxious. Just looking at your goals regularly, research says, makes you 90% more likely to achieve your goals.

- Ask the person who reports to me to share one goal with me. Hearing about other people’s goals also provides good context for our perspective–pulls us out of the echo chamber of our own anxiety.

- Develop a discipline in how I evaluate circumstances by looking also for what’s going right, what’s getting done: Then, affirm the person (and yourself for that matter) for positive results. Resist the temptation to focus strictly on what needs improving.

Of course, there are thousands of details to the context of our lives, and thousands more strategies to focus on that context so that we don’t suffer from a proverbial myopia. To the degree that we seek to take in the bigger picture, pay attention to the broader view, and step outside of ourselves to see the grander view of the sky’s horizon, we step back from worry and toward a better view of life, of others around us, and of ourselves.

Research shows that stress and anxiety can lead to mental toughness and increase clarity about life’s challenges and opportunities. It can also result in greater appreciation for one’s circumstances, and contribute to a sense of confidence . This confidence becomes a foundation you build every time you overcome an obstacle, and this is the best, most long-lasting kind of confidence you can have. Hard fought and well earned, indeed.

In the next blog, I’ll take on the importance of retrospection and circumspection.

Question: What do you do to keep focused on the bigger context in order to maintain good perspective in your life?